Bison Biology: The History and Future of America's Largest Mammal

- Caleb Mullenix

- Oct 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 6, 2025

Standing up to six feet tall and weighing over 2,000 pounds, the American bison represents one of North America's most remarkable biological success stories. As the continent's largest terrestrial mammal, bison have shaped grassland ecosystems for hundreds of thousands of years, survived near-extinction, and now serve as a powerful symbol of conservation achievement. Understanding bison biology provides students with invaluable insights into ecology, evolution, conservation science, and the complex relationships between human activity and wildlife populations.

Physical Biology and Distinctive Characteristics

The American bison (Bison bison) possesses several extraordinary anatomical adaptations that distinguish it from other bovines and enable survival in harsh North American climates. Adult males, called bulls, can exceed 2,000 pounds and stand six feet tall at the shoulder, while females (cows) typically weigh 1,000-1,200 pounds. These massive herbivores are characterized by their pronounced shoulder hump, which contains powerful muscles essential for snow plowing during winter foraging.

Perhaps most remarkable is the bison's winter coat, which contains approximately ten times the number of primary hairs per square inch compared to domestic cattle. This dense fur provides exceptional insulation, allowing bison to withstand temperatures as low as -40°F. During spring, bison shed these thick coats in dramatic fashion, often rubbing against trees and rocks until large patches of fur hang from their bodies like tattered blankets.

Bison horns curve inward rather than outward, an adaptation favoring charging behavior over the horn-locking combat seen in other bovines. Their comparatively slender hindquarters and massive front shoulders create a distinctive profile that reflects their evolutionary adaptation to life on open grasslands.

Evolutionary Journey Across Continents

The bison's evolutionary story spans millions of years and multiple continents. The genus Bison first appeared in Asia during the Early Pleistocene epoch, approximately 2.6 million years ago. However, bison did not reach North America until much later, arriving between 195,000 and 135,000 years ago during the late Middle Pleistocene period.

These ancestral bison descended from Siberian steppe bison (Bison priscus) that migrated across the Beringia land bridge. Upon reaching North America, bison rapidly diversified into multiple species, including the massive Bison latifrons, the largest bison species ever documented. Modern American bison evolved from Bison antiquus approximately 10,000 years ago at the end of the Late Pleistocene epoch.

The ecological impact of bison arrival was so profound that paleontologists use their presence to define the Rancholabrean faunal stage, demonstrating how a single species can fundamentally alter entire continental ecosystems.

Ecological Architects of the Great Plains

Before European colonization, an estimated 30 to 60 million bison roamed North America, primarily across the Great Plains. These vast herds functioned as ecosystem engineers, fundamentally shaping grassland ecology through their grazing, wallowing, and movement patterns.

Bison influenced vegetation diversity and soil composition in multiple ways. Their selective grazing promoted plant species diversity by preventing any single grass species from dominating. Wallowing behavior created circular depressions in the soil that altered water drainage patterns and created unique microhabitats supporting different plant and animal communities.

As nomadic grazers, bison dispersed seeds across vast distances in their shaggy coats and deposited nutrient-rich dung that insects and bacteria decomposed, recycling essential nutrients throughout grassland soils. This constant movement and nutrient cycling made bison the primary architects of North American grassland ecosystems, influencing biological processes more profoundly than any other large herbivore.

The Great Collapse: A Conservation Crisis

The 19th century witnessed one of the most dramatic wildlife collapses in recorded history. Beginning around 1830, systematic bison slaughter accelerated with railroad construction in the 1860s, which facilitated both human settlement and transportation of hides and meat to eastern markets.

The statistics from this period reveal the scale of destruction. In 1870 alone, hunters killed an estimated 2 million bison on the southern plains. Between 1872 and 1874, approximately 5,000 bison died daily, totaling 5.4 million animals in just three years. Commercial hunting operations employed teams of hunters who could kill hundreds of bison per day, processing only the most valuable parts while leaving carcasses to rot on the prairie.

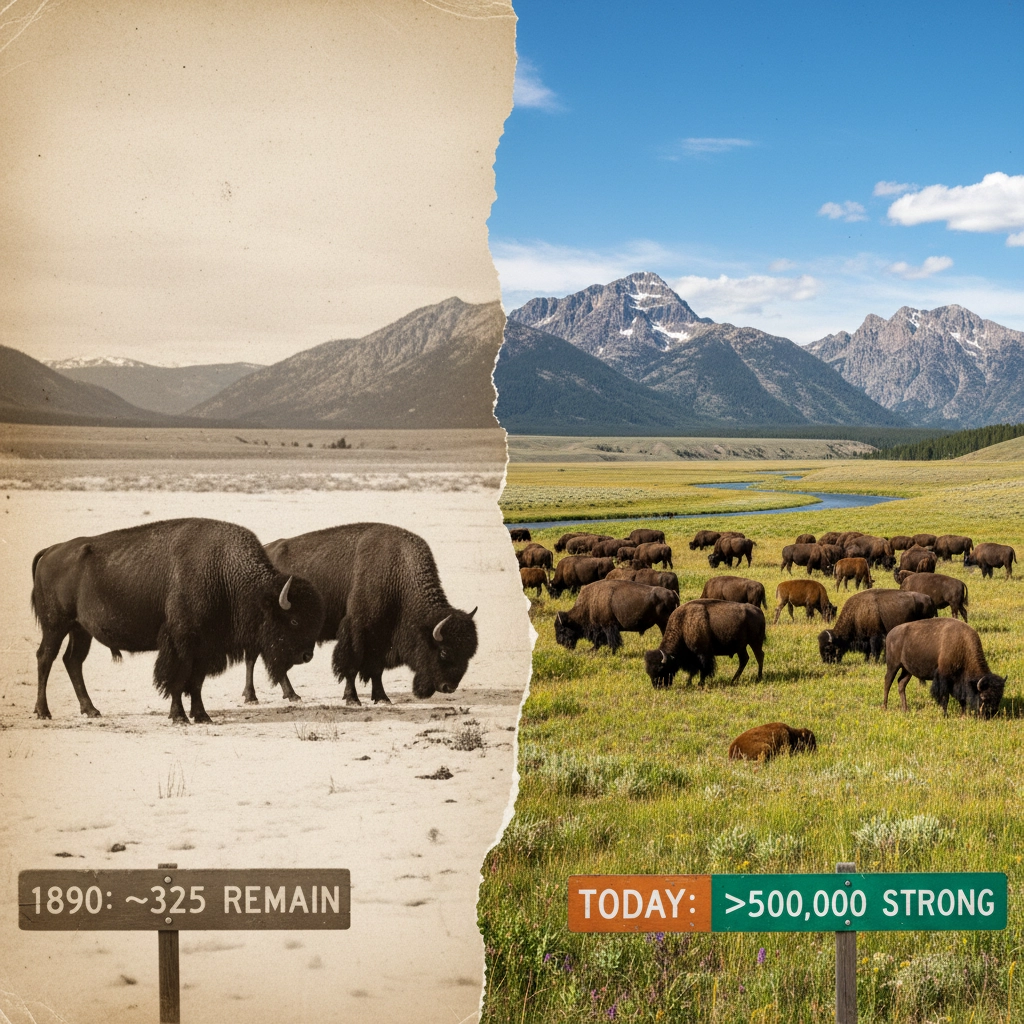

By 1884, the American bison population reached its absolute nadir with only 325 wild individuals remaining across the entire United States. Yellowstone National Park harbored just 24 of these survivors, representing the only continuously wild, free-ranging population in the continental United States.

Conservation Recovery: From 325 to 500,000

The near-extinction of bison catalyzed one of America's first major wildlife conservation movements. Dedicated ranchers and conservationists gathered remnants of existing herds to prevent complete species loss. During this population bottleneck, genetic diversity contracted severely as the entire species descended from approximately 541 individuals.

Recovery efforts gradually increased the population to roughly 1,000 bison by 1910. Today, the United States supports approximately 500,000 bison, including 5,000 in Yellowstone National Park. This remarkable recovery transformed bison from an endangered species into a genuine conservation success story, though most modern bison live in managed herds rather than free-ranging populations.

Yellowstone maintains special significance as the only location in the continental United States where wild, free-ranging bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times. The park also contains one of only three remaining genetically pure herds in North America, with the others located in Utah and South Dakota.

Modern Biology and Social Behavior

Contemporary bison exhibit fascinating social behaviors that reflect their evolutionary adaptations to grassland environments. For most of the year, herds segregate by sex, with females and calves forming maternal groups while males form bachelor herds. This segregation reduces competition for resources and allows specialized behavior patterns to develop.

During summer breeding season, dominant bulls temporarily join female herds and compete for mating opportunities through physical combat involving head-butting and horn-based wrestling matches. Pregnancy occurs in fall, with females carrying calves through winter for births in mid-spring, maximizing calf survival chances through the following winter.

Newborn calves weigh approximately 50 pounds and possess reddish fur that gradually darkens to brown. Remarkably, calves stand and walk within an hour of birth, an essential adaptation for survival in open grassland environments where predators pose constant threats.

Bison communicate primarily through scent rather than sound, using pheromones for complex social interactions, particularly during reproduction. However, they also vocalize with grunts, snorts, and growls to convey immediate information about threats or social status.

Two Subspecies: Plains and Wood Bison

North America supports two distinct bison subspecies: Plains Bison (Bison bison bison) and Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae). Plains bison are generally smaller with more rounded humps, while Wood Bison are larger with more pronounced shoulder humps and longer legs adapted for navigating forested environments.

Geographically, Wood Bison inhabit northern regions including Alaska and northern Canada, while Plains Bison predominate in southern areas including the Great Plains and Yellowstone. Understanding these subspecies differences provides students with insights into how populations adapt to specific environmental conditions over evolutionary time.

Educational Opportunities and Future Conservation

The bison's remarkable journey from abundance to near-extinction and back to recovery offers students powerful lessons about ecology, conservation biology, and human impact on natural systems. Educational expeditions to locations like Yellowstone provide opportunities to observe these magnificent animals in their natural habitat while studying ecosystem dynamics, conservation challenges, and scientific monitoring techniques.

Modern conservation efforts focus on maintaining genetic diversity, managing human-wildlife conflicts, and restoring bison to their historical ecological roles. Students can explore how scientists use GPS collars, genetic sampling, and population modeling to monitor bison herds and make informed management decisions.

The American bison's story demonstrates both the fragility of even abundant wildlife populations and the power of dedicated conservation action. As America's national mammal, bison continue to symbolize the ecological richness of North America's past and the possibility of restoration for its future, providing endless educational opportunities for students to explore the complex relationships between science, policy, and conservation success.