Saving Florida's Vanishing Coral Reefs: How Students Can Lead the Way

- Caleb Mullenix

- Oct 23, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 27, 2025

The functional extinction of Florida's staghorn and elkhorn corals represents one of the most profound environmental lessons of our time. While the loss of these iconic reef-builders signals an ecological catastrophe, it also presents educators with an unprecedented opportunity to inspire the next generation of marine conservationists. Understanding how to transform this crisis into meaningful action requires careful preparation, thoughtful curriculum design, and hands-on educational experiences that connect students directly to the urgent realities of marine ecosystem collapse.

Understanding the Scope of Coral Loss

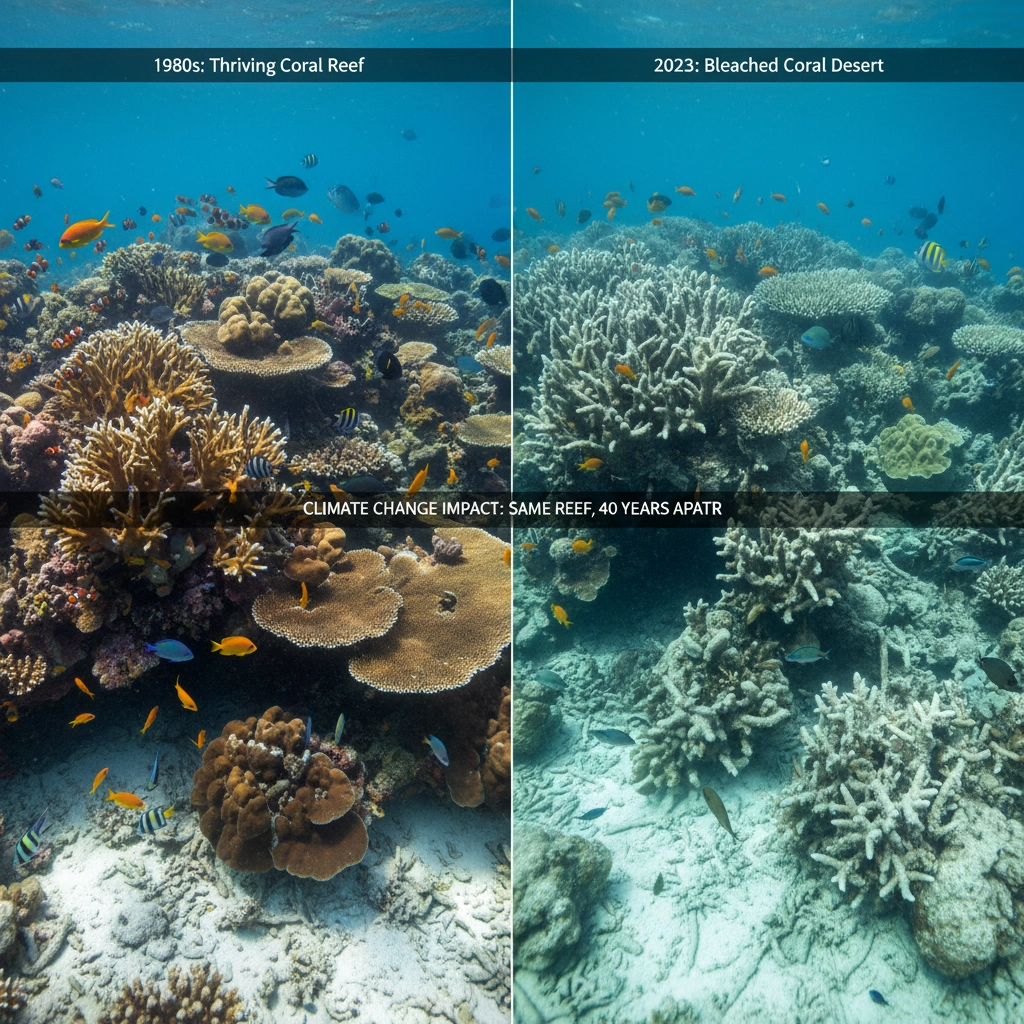

The 2023 marine heatwave fundamentally altered Florida's coral reef ecosystem in ways that demand immediate educational attention. Scientists documented mortality rates reaching 98-100% across the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas, with even offshore southeast Florida experiencing 38% coral death. This catastrophic event reduced the remaining populations to approximately 150 elkhorn and 300 staghorn corals across the entire Florida reef system: a stark reminder of how quickly entire ecosystems can collapse under climate pressure.

Educators must emphasize to students that this decline did not occur overnight. These coral species experienced a 97% population decline in the 1980s due to white band disease, followed by decades of additional stressors including warming waters, ocean acidification, and coastal pollution. The 2023 heatwave: with temperatures 2.2 to 4 times higher than previous records: delivered the final blow to populations already hanging by a thread.

This progression from abundance to functional extinction provides students with a powerful case study in cumulative environmental impacts. Encourage students to examine how multiple stressors interact to create tipping points in natural systems, demonstrating the interconnected nature of environmental challenges they will face as future scientists and conservationists.

The Meaning of Functional Extinction in Marine Ecosystems

Functional extinction represents a critical concept that students must thoroughly understand. Unlike complete species extinction, functional extinction occurs when populations become so depleted that they can no longer fulfill their ecological roles, even though individual organisms still survive. In the case of staghorn and elkhorn corals, the remaining populations cannot provide the reef-building services, habitat complexity, or wave protection that once defined Florida's marine ecosystems.

Why this loss matters now:

Ecosystem function: Branching corals create essential three-dimensional habitat and nursery grounds for fish and invertebrates; their decline fragments food webs and reduces biodiversity.

Economic stability: Healthy reefs support local jobs through fisheries, diving, and tourism; coral loss undermines livelihoods, school-community partnerships, and regional economies.

Coastal protection and safety: Reef structures dissipate wave energy and reduce storm surge and erosion; when coral architecture collapses, coastal infrastructure and communities face higher risk.

Education and culture: Reefs are living classrooms and cultural touchstones; their degradation limits authentic learning opportunities and community connections to place.

Students studying this collapse must recognize that functional extinction often precedes complete species loss, creating narrow windows of opportunity for conservation intervention. This reality underscores the urgent timeline facing current and future marine biologists and educators: act quickly, act safely, and act through coordinated, evidence-based restoration and protection.

Transforming Crisis into Educational Opportunity

The staghorn and elkhorn coral crisis provides educators with a compelling framework for engaging students in real-world conservation challenges. Begin by establishing clear learning objectives that connect this specific case study to broader principles of marine ecology, climate science, and conservation biology. Students should understand both the scientific mechanisms driving coral decline and the human activities contributing to these changes.

Create structured learning experiences that allow students to analyze primary research data from the coral monitoring studies. Encourage students to examine the temperature records, mortality surveys, and population assessments that led scientists to declare functional extinction. This direct engagement with scientific evidence helps students develop critical analysis skills while understanding the rigorous documentation required for conservation decisions.

Design classroom activities that explore the interconnected nature of reef ecosystems, demonstrating how coral loss affects fish populations, coastal protection, tourism economies, and local communities. Students should recognize that environmental problems require interdisciplinary solutions combining biology, chemistry, economics, and social science approaches.

The Power of Field-Based Marine Science Education

Classroom instruction alone cannot fully convey the urgency and complexity of marine conservation challenges. Students require direct exposure to reef environments, research methodologies, and conservation practices to develop the deep understanding necessary for effective environmental stewardship. Field-based educational experiences provide irreplaceable opportunities for students to witness ecosystem changes firsthand while developing practical research skills.

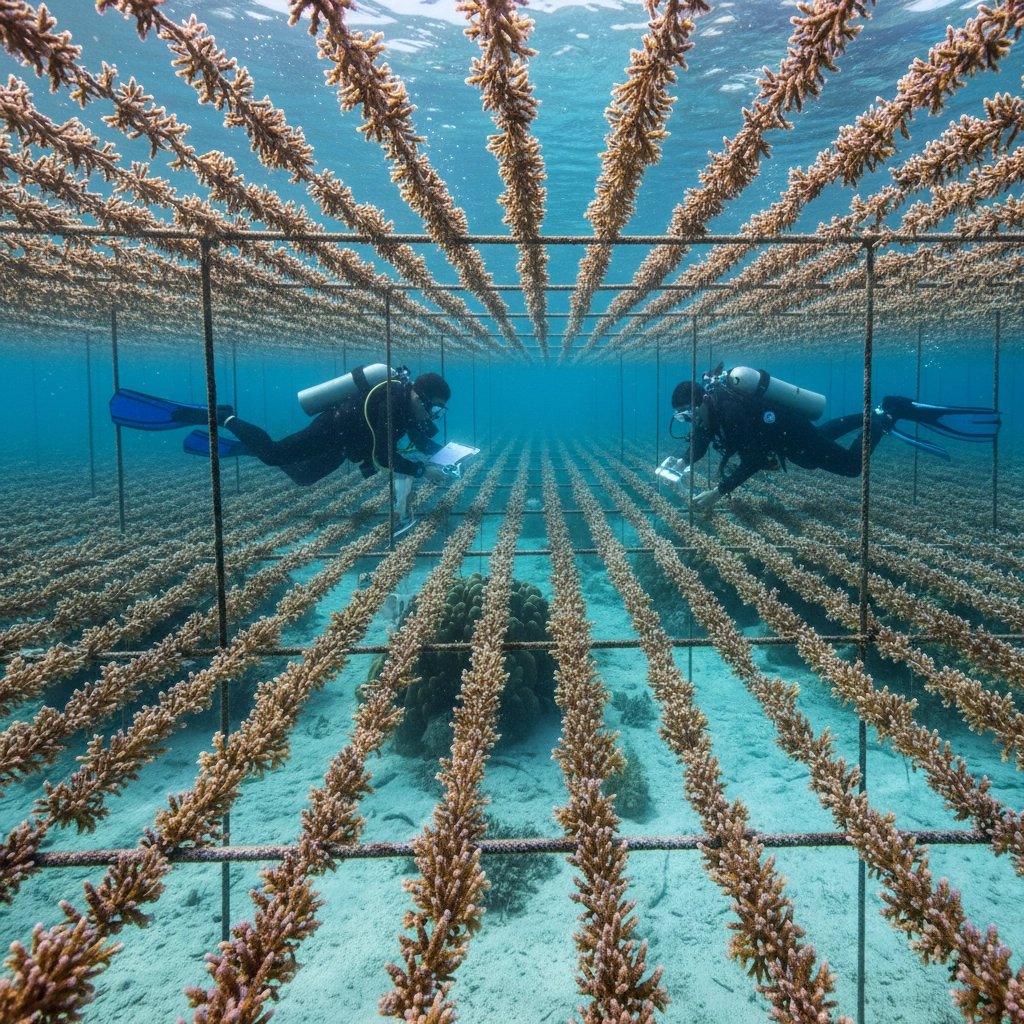

Educational expeditions to Florida's coral reefs allow students to observe both degraded reef areas and active restoration sites, creating powerful contrasts that illustrate both the scale of environmental challenges and the potential for human intervention. Students can participate in coral monitoring protocols, water quality assessments, and restoration activities that demonstrate the hands-on nature of marine conservation work.

These experiential learning opportunities should include interactions with professional marine biologists, restoration specialists, and conservation managers who can share their career paths and daily responsibilities. Students benefit enormously from understanding how their classroom studies connect to real-world career opportunities in marine science and environmental management.

What Students Can Do Right Now

Prioritize safety, supervision, and permits. Coordinate with site managers, follow dive/snorkel training requirements, and use reef-safe practices.

Hands-on conservation and restoration (with qualified partners):

Assist coral nursery care: clean nursery trees, check ID tags, and record growth/health metrics under supervision.

Support permitted outplanting and maintenance: help transport fragments, prepare substrates, and monitor survivorship as allowed by managers.

Conduct in-water monitoring: follow established protocols for transects, photo quadrats, and temperature logging; practice buoyancy control and no-touch rules.

Citizen science and data contributions:

Document bleaching, disease, or mortality events with standardized forms and geotagged photos for local monitoring programs and marine sanctuaries.

Contribute water quality, temperature, and species observations to community databases used by researchers and managers.

Education and advocacy:

Present findings to classmates, parents, and school boards; host reef-safety briefings and reef-safe sunscreen campaigns.

Draft respectful letters to local officials supporting marine protected areas, water-quality improvements, and reef-friendly coastal policies.

Reduce personal and campus climate impacts:

Conduct a school energy and travel audit; recommend measurable reductions in electricity use, single-use plastics, and high-emission travel.

Choose low-impact boating and mooring practices; never anchor on reefs and follow posted guidelines.

Career exploration and skill-building:

Pursue first aid, water-safety, and snorkeling/diving certifications with certified instructors.

Build data literacy, mapping, and communication skills to support field teams and outreach.

Building Scientific Literacy Through Coral Conservation

The coral extinction crisis offers exceptional opportunities to develop students' scientific literacy and critical thinking skills. Encourage students to examine the peer-reviewed research documenting coral decline, including the October 2025 study published in Science that formally declared functional extinction. Students should analyze the methodology, data interpretation, and conclusions drawn by researchers while developing their own understanding of scientific evidence.

Create assignments that require students to evaluate different conservation strategies, including gene banking programs, coral nurseries, and assisted migration techniques. Students should assess the strengths and limitations of each approach while considering the practical challenges of implementing conservation programs in marine environments.

Emphasize the importance of long-term ecological monitoring and data collection in understanding environmental changes. Students should recognize that the coral decline documentation required decades of consistent observation and measurement, highlighting the persistence and dedication required for effective environmental research.

Developing Future Conservation Leaders

The next generation of marine conservationists will face unprecedented challenges requiring innovative solutions and sustained commitment. Educators must prepare students not only with technical knowledge but also with the leadership skills, ethical frameworks, and collaborative abilities necessary for effective environmental stewardship.

Encourage students to develop their own conservation project proposals addressing specific aspects of coral reef protection or restoration. These projects should demonstrate understanding of scientific principles while proposing realistic, achievable interventions that could contribute to broader conservation efforts. Students should present their proposals to peers, parents, and community members, developing communication skills essential for conservation advocacy.

Connect students with local environmental organizations, marine research institutions, and conservation groups where they can contribute to ongoing projects while gaining practical experience. Many organizations welcome student volunteers for beach cleanups, water quality monitoring, and educational outreach programs that provide meaningful service learning opportunities.

Preparing Students for Marine Science Careers

The coral crisis highlights the critical need for well-trained marine biologists, restoration specialists, and conservation managers. Educators should help students understand the educational pathways and skill development necessary for careers in marine science and environmental protection.

Emphasize the interdisciplinary nature of modern conservation work, which requires expertise spanning biology, chemistry, computer science, engineering, and social science. Students should understand that effective marine conservation requires collaboration across multiple disciplines and sectors, from academic research to government policy to community engagement.

Encourage students to pursue advanced coursework in mathematics, chemistry, and biology while developing strong writing and communication skills. These foundational capabilities enable students to contribute effectively to research teams and conservation organizations throughout their careers.

Take Action: A Step-by-Step Plan for Teachers and Students

In the next two weeks:

Align objectives: Define clear learning goals linked to reef ecology, safety, and community service.

Prepare safely: Review risk assessments, parent communication, medical and permission forms, and emergency procedures; designate roles for teachers and chaperones.

Build background: Assign readings on Florida coral decline and restoration; practice data sheets and equipment use in class.

In the next 30–60 days:

Partner formally: Schedule a field day or virtual lab with a restoration organization or sanctuary program; confirm permits, supervision ratios, and contingency plans.

Train and brief: Conduct swim tests and safety briefings; practice reef etiquette, buddy systems, and gear checks; require reef-safe sunscreen.

Collect baseline data: Begin campus- or shoreline-based monitoring (water temperature, turbidity, litter surveys) to build skills before reef work.

This semester:

Execute a service-learning project: Maintain a coral nursery, assist with monitoring, or run a reef-safety outreach event; document methods, data, and outcomes.

Communicate results: Create posters, short reports, or presentations for families, administrators, and local officials; recommend concrete next steps.

Reflect and iterate: Evaluate what worked, update protocols, and plan follow-up actions with safety and stewardship in mind.

All year:

Reduce impacts: Implement energy, waste, and travel reductions at school; track metrics and celebrate progress.

Stay engaged: Participate in citizen science alerts during heatwaves or disease events; share observations promptly with partners.

By emphasizing safety, preparation, respect, communication, and supervision at every stage, educators can transform concern into responsible action. Careful planning, clear procedures, and hands-on, experiential learning will protect students, protect reefs, and maximize educational impact—ensuring that learning is rigorous, service-oriented, and resilient in the face of a changing ocean.

Comments